We’ve always loved Santiago Solari here at pegamequemegusta, so when we saw this interview, conducted by Claudio Mauri, on canchallena this morning, we decided to translate it for your pleasure and edification.

We miss his fine articles in El País, several of which we translated in the past. They’ve more or less been abandoned since he got towards the more serious end of Real Madrid’s youth coaching system: last week, with Zidane leaving the B-team to become manager, Solari took over the under-18s (table). He coached successive U-16s teams to their respective titles, last winning 26 out of 28 matches and drawing the other two.

Mauri is quite insistent as to why he hasn’t stepped up to take over a real manager’s job yet, and it is a bit of a puzzler. Real Madrid president Florentino Pérez apparently suggested he become Zidane’s assistant, but Zizou already had his own staff from the Real B-team. Yet if Pérez loves him so much, surely he could get a job elsewhere. After all, fellow articulate, loveable, rogue analyst Facundo Sava is even managing Racing now, thrashing Boca 4-2 last night in his debut (albeit a friendly). Solari isn’t biting, though, nor is he eschewing the limelight out of some misplaced and feckless sense of nobility, like a session musician or a blogger. He genuinely does seem to believe in apprenticeship.

There’s also an interesting debate regarding the usefulness of a club like Real’s academy, as per Barney Ronay’s piece today. They process so many players that almost all end up shot out like spores from a thriving mass of fungus. Is this just the inevitable result of searching for the very best? Or are they being groomed as future leverage against other clubs? The transfer ban may see some of Solari’s charges come through. We’ll see. In the meantime, check him out, or pegame, que me gusta.

-

I asked around for a take on your work here and they tell me you’re “the most outstanding coach” at Real Madrid’s academy. Are they exaggerating?

-

Most certainly.

-

On the other hand, they say you’re a “slowpoke” in the sense that you like to take things easy, something that doesn’t really fit with a being a manager, given how harsh and unforgiving life in primera can be.

-

I was born and raised in primera. My aul’fella played for 15 years and then managed for another 20 after that. Then I played for fifteen years. It’s all I know. That’s the story of my life. Maybe that’s why I’m pretty relaxed about things.

-

Is it true you were close to becoming Zidane’s assistant? Florentino Pérez has a high opinion of you.

-

I hope so, I’m grateful and every day I do my job to maintain that high opinion. Zizou is with the first team now with the same staff he had at Real Castilla, and I’m working with the Juvenil A. We’ve always got on well, ever since we played together. My dressing room’s 30 metres from his and I’m always on hand if he needs me.

-

Florentino Pérez has changed 11 managers in 12 years in charge. Is there more patience with the youths?

-

At this club the same is required at all levels. The pace of change of the first team is that of elite competition. With the youth team they respect the time needed to develop players.

-

Barcelona’s La Masía is a school with a particular identity. Does Real Madrid have one? If so, what is it?

-

With 114 years as an institution and ten European Cups, Real Madrid is, officially, the greatest club of the last century, not to mention the most important in the world owing to its prestige and stature. I can’t think of a more relevant identity in football terms than Real Madrid’s. And the youth team is the club, a club with a culture of winning that, through humility, hard work and self-control, always aspires to be the best. Now, if you’re referring only to football, of course, we work to produce players and teams who are brave and get forward, who dominate all aspects of the game, have a winning mentality and exemplary behaviour. If you want to talk about style and method, though, they’re going to have to expand the sports section.

-

How would you define yourself as a manager? You’ve been exposed to Argentine, Spanish and Italian schools, but which has made more of an impression?

-

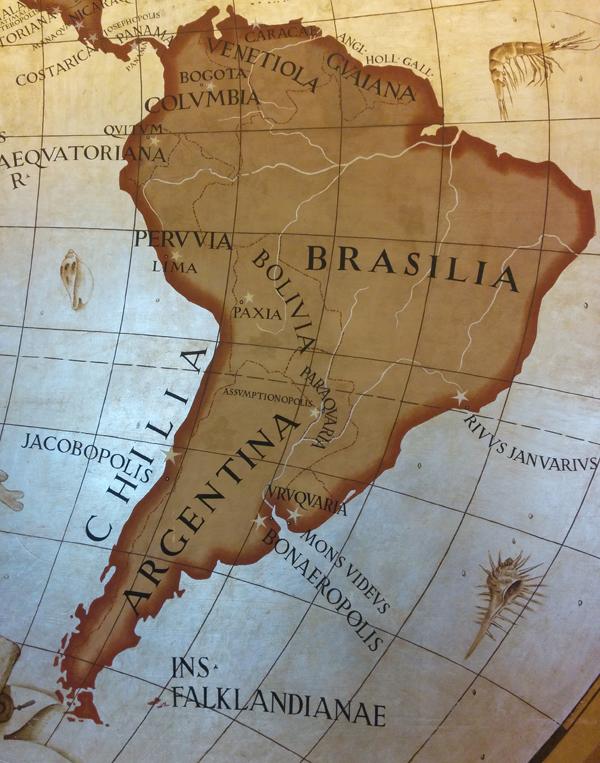

I was in Uruguay and Mexico, too… Every country lives its football in its own way. They’re all equally as exciting, if not always as much fun. The football cultures that have most influenced me were Argentina and Spain, the two places I’ve spent most time.

-

Which manager influenced you the most? What tactical system do you use?

-

All the managers I had taught me something. The best ones are a blessing, the bad ones edifying. With regard to systems, they’re almost always something to aim at, not a starting point. What’s more important is who your players are, their roles, the style the coach wants to achieve; strategy, tactics, the other team, the pitch, etc. The system is the last thing on your mind, maybe the least important thing.

-

Do you enjoy the business as much as when you were playing?

-

Nothing compares to playing. I love football; now I enjoy it from another perspective. And whenever I can, I play the odd match with the old timers.

-

What were the strong points of your title-winning teams?

-

Coaching the A & B Under-16s teams [Cadete A & B] in successive years was a beautiful experience. We won the tournament both years, but in the second year you could really see and appreciate how much they’d grown and learned, both as individuals and as a team. The greatest success, without a doubt, was that we didn’t lose any of them: they all made the grade up to Juvenil C (U-17). With the Juvenil B this season we’ve formed a really competitive team, with second place nine points behind us. Since last week [youth teams reshuffle] the challenge is to get to grips with the Juvenil A, who are currently fourth and have to improve. There’s also the question of challenging for the Youth Champion’s League.

-

You’re more dependent on results now, then, with less of an emphasis on development?

-

Football is always about improving, even in the first team. Results always matter, too, even with the youth teams – at least when you’re forming players for the highest levels of the game.

-

Sometimes in Reals’ starting 11 there’s only one youth player, like Carvajal, who even had to go to Germany to get first team football, before coming back and earning his place. Do you feel you’re coaching players for other clubs’ first teams?

-

On the contrary, it’s an enormous satisfaction, and it’s even tough to compete with Real Madrid on that score, too: besides the eight youth players currently in the first team squad, there are more than a hundred players that came through our youth system playing in the first division, and fifty more in the lower divisions worldwide. Almost all the teams in the league have players who were trained by Real Madrid. Those kinds of numbers are a source of pride for us.

-

Often in Argentina youth players are promoted to the first team before they’re mature enough in order to fill the gaps left by clubs’ policy of selling players abroad…

-

Yeah, it’s true. In Argentina often we don’t respect the time players need to mature.

-

How long do you see yourself coaching youth teams? Do you plan to manage in primera, and, if so, when?

-

I believe in learning, not just for footballers but for coaches – and, obviously, for directors, too. Yes, I want to manage in primera. All in good time.

-

Are there any Argentine players that you’ve coached or are coaching now?

-

No.

-

In Argentina’s youth teams, there’s a lack of full backs and deep-lying midfielders. Can you think of a solution to the problem?

-

Yes, several, but asking me that’s like asking for the formula for Coca Cola.

-

There’s a general impression that young players nowadays aren’t as interested in learning about the game, living it, that there are too many distractions. How do you fight against that?

-

I think the opposite is the case. No kid is made to play football. It’s a choice and there’s no other way to become a professional football player than through dedication and sacrifice. A teenager who goes to school for six or seven hours a day and then has to train for another three hours, and who on Saturdays goes to bed early because he has to play on Sunday, is an example of application and dedication. He has too little time for other activities.

-

You’ve always taken a keen interest in cultural matters. Do you talk about those kinds of things to your players?

-

I’d call it a survival instinct… And yeah, I try to explain that not all of them are going to make a living playing football, and certainly not forever.

-

In an interview with El Gráfico in 2011 you said that you liked Barcelona and that Guardiola’s influence on the team was clear. Although your Madrid credentials aren’t in question, you have a guardiolista bent, don’t you?

-

No, I don’t think so. I’d prefer to keep my hair.

-

What do you make of Messi? Is there anything left to say about him?

-

Messi is one of those things that you know you’re not going to see again. There’s nothing original to say about him. It’s him who’s original.

-

What do you think about Argentine football?

-

I follow it as much as I can. With the last championship it was difficult as I still haven’t worked out how the fixture list was concocted…

-

When you were with San Lorenzo in 2008, [proxy president] Tinelli’s contribution was key. Do you see him becoming president of the AFA ?

-

The AFA is in serious need of reform, in both form and content. Tinelli is a self-made man with unquestionable administrative ability. I’m sure he could do a good job, as he has done with San Lorenzo [Libertadores champions 2014].

-

If you could manage a club in Argentina some day, which one would it be?

-

One of the clubs I played for.

-

Gallardo, Coudet, Sava, Cocca, Bassedas, they’re all contemporaries of yours who are managing in top divisions; some have even won titles. Are you on a slightly different wavelength?

-

I don’t know. I hope they’re all enjoying themselves as much as I am.

-

Why haven’t Argentina won anything since 1993?

-

With a reformed AFA I hope the answer will come of its own accord. In any case, I hope we win something with El Tata [Martino] in charge. He’s a great manager and a great guy.

-

Lots of people continue to question Messi. What do you think?

-

No point arguing with fanatics.